The Korean War: Reflections on Shared Australian and Canadian Military Experiences

The Ronald Haycock Lecture in War Studies recognizes the long-term contributions of Professor Haycock to the War Studies Programme, the flagship of the Graduate Studies and Research Division at Royal Military College.

The Canadian and Australian Armies have a long, common military heritage going back more than a hundred years — to the Boer War, when Canada and Australia both contributed Mounted Rifles units to General Hutton’s 1st Mounted Rifles Brigade.Then, in the First World War, it was alongside the Canadian Corps that Australia’s General Sir John Monash and the Australian Corps fought what is arguably Canada’s and Australia’s greatest battle of that war — at Amiens on 8 August 1918 — a battle described by Germany’s General Ludendorff as ‘the black day of the German Army’ and which was also the first ‘ABCA’ Battle—including forces from Britain, the United States, Canada and Australia, as well as France.I have already written about that shared heritage in an earlier issue of Canadian Military Journal [Volume 3, Number 3].

Now, with the 50th anniversary of the end of the Korean War being celebrated this year, it seems appropriate that the 2003 Haycock Lecture should focus on the Korean War—when Canadians alongside Australians once again made their mark. Some might say that the Korean War has been re-visited enough over the last couple of years. But this presentation offers a different perspective that hopefully justifies the continued consideration of that war. The attention may also be worthwhile given the fact that the stand-off on the Korean peninsula, set in place with an armistice signed in 1953, remains an enduring source of concern for all of us to this day. Having said that, the focus here is not on a regurgitation of the well-known phases of the Korean War. Rather the focus is on comparing the Australian and Canadian experiences.

While in Canada, my studies were focused on comparing and contrasting the experiences of the Australians and Canadians on military operations over the last century.It was found that the two countries chose divergent courses for their armed forces during the Cold War, and particularly after the Korean War. Canada emphasized Atlantic alliance commitments and peacekeeping, while Australia focused more on South-East Asia, war-fighting and self-reliance. Yet both armed forces have retained enduring parallels. Indeed, since the end of the Cold War, their paths have largely re-converged, with both contributing similar forces to Namibia, the Gulf War, Cambodia, Western Sahara, Somalia, Rwanda, Mozambique, East Timor, Sierra Leone, and Afghanistan in 2002—where Canadian infantry and special forces operated alongside Australians as war-fighters. Time and again, they have made expeditionary force contributions alongside their major allies, successively Britain and the United States, and frequently in the same locations. Given the reconvergence and the opportunities to once again work together, it seems appropriate to reflect on the time Australians and Canadians went to war together in Korea, before the divergence of force trajectories became most noticeable during the Cold War.

What follows therefore, is a brief discussion on the lead-up to the war, a look at the initial Canadian and Australian responses to the onset of war, their force contributions, the battle of Kap’yong, the formation of the Commonwealth Division, the growing American influences, restraints on cooperation, and a short consideration of the war’s diplomatic effects. The conclusion provides a reflection on the Canadian and Australian ‘ways of war’ as they emerged from the Korean War.

AWM ART 28077

HMAS Sydney in Korean Waters, 1951-52.

Painting by Ray Honisett.

Lead Up to War

In the years prior to the Korean War, particularly during the Second World War, Australia had become part of the US economic and security orbit, but this was largely a result of ad-hoc wartime measures that temporarily expired at war’s end. Canada, however, established more formal and lasting security and economic ties with the United States in 1940 and 1941. The United States would not see the need formally to tie Australia and New Zealand into its alliance system until after the onset of the Cold War—particularly following the Communist take-over in China and the commencement of the Korean War. Moreover, trade and security ties with Britain would still feature more prominently for Australia and New Zealand following the end of the Second World War than they would for Canada.

Thankfully, the surrender of Japan in 1945 had obviated the need for the Australian and Canadian forces, assigned to General MacArthur’s command, to invade Japan. But the prospects of using American equipment and supplies that MacArthur had demanded as a pre-condition to their troops contributing to the planned invasion reflected the early stages of a re-orientation to American equipment and standards and growing American influence that would affect the Canadian Forces as well as the Australians. For Canada, that reorientation had been confirmed in Recommendation 35 of the Permanent Joint Board of Defence (PJBD), which switched the model for Canada from Britain to the United States. Australia would take a slower course to that destination. In any event, with war surpluses and financial constraints, it would not be until the later stages of the Korean War that this policy could be implemented to any significant extent, even for Canada.

For Australia, American links with the South Pacific had lacked the historical foundation of the Pan-American system. The point really was that, however much Australia and New Zealand might see NATO as a precedent for their region, the United States just did not want to take on such an obligation, and saw no reason why it should. For the Americans, at least prior to the Korean War, their security ‘perimeter’ excluded Australia and New Zealand just as much as Korea. Thereafter, Australian diplomatic efforts would focus on the objective of ensuring US regional engagement for over a generation to come, seeking to redress the initial post-war downturn in relations with the United States. The maintenance of expeditionary forces would be a key instrument used in pursuit of this policy.

With concerns about security in the Asia-Pacific region in mind, Australia’s Secretary of Defence, Sir Frederick Shedden, tried to raise Canadian interest in a Pacific Defence Pact in 1947. Canada’s Minister of National Defence, Brooke Claxton, and Secretary of State for External Affairs, Lester B. Pearson, responded coolly to the idea. Claxton argued that it was up to the United States to initiate a Pacific regional security system, while Pearson stressed the apparently greater threat in the Atlantic precluding substantial commitments in the Pacific. While Australia still placed emphasis on British Commonwealth defence measures, Mackenzie King, Canada’s Prime Minister until 1948, was eager to remain at arms length from the British Empire and even, at that stage, from the United Nations. Indeed, the time for closer Canadian cooperation with Australia was not yet ripe. The opportunity for fence mending would have to wait until the departure of Mackenzie King in 1948 and Australia’s fiery External Affairs Minister, Dr. Herbert Evatt, in 1949. Even with such changes, however, the opportunity for greater collaboration would not be taken up until the outbreak of the Korean War. At that point, both Canada and Australia would affirm the principle that the defence of their nations was best achieved as far away from their own shores as possible. What is more, the absence of any formally-established mechanisms for cooperation and combined planning left Canadian and Australian policymakers excessively at the mercy of strong personalities within their bureaucracies, and the vagaries of shifting US foreign and defence policy. Pre-occupied with their immediate self-interests, Canadian and Australian policy-makers were unable to see the longer-term benefits and mutual self-interest of closer cooperation with each other. Such cooperation conceivably would have given both countries greater diplomatic leverage to further their own national interests.

Onset of the Korean War

At the outset of the Korean War, the Australian government committed itself to an emergency Three Year Defence Plan, and the expansion of the Army, including the introduction of National Service for home defence only. Canada similarly raised defence expenditure and set out to expand the force by 12 percent to 47,185 troops. In contrast, the Australian Army had an authorized permanent-force strength of only 19,000, but by June 1950 the number of soldiers on full-time duty was only 14,651. This number would grow to 29,104 during the Korean War (supplemented by 29,250 National Servicemen per year trained for homeland defence and the Citizen Military Forces). Canada’s Prime Minister, Louis St. Laurent, argued in support of the war from a realist perspective saying: “I am simply asking you to pay an insurance premium that will be far less costly than the losses we would face if a new conflagration devastated the world.” By the same token, Canada was eager for the endorsement of the United Nations Security Council. Canadian historian, Denis Stairs, argued that “without this formal involvement of the United Nations the government in Ottawa would no more have embroiled itself in the conflict in Korea than it did later in the war in Vietnam” (His assessment would prove accurate for the war in Iraq in 2003 as well.) According to Stairs, “Canadian officials felt it was essential to moderate and constrain the course of American decisions. In attempting to do so, they acted in concert with other powers of like purpose, and their instrument was the United Nations itself. They met with only marginal success....”The official remarks from 1951 and Stairs’ observations appear to be timeless, reflecting Canada’s cautious foreign policy approach. They also reflect a continuing contrast in the greater willingness of Australia to gain political mileage from its relatively small contributions of expeditionary forces. As a classified official Canadian report observed in 1951:

We prefer not to make commitments we are not reasonably certain we can carry out. For this reason we frequently have no definite policy on a question until almost the last minute. This makes it difficult for our representatives to engage in discussion with the Americans before American policy has become too firm to be altered.... Despite what we have done and are planning to do...many Canadians have a somewhat unconscious feeling that we may not be doing our full share. This puts us on the defensive in our dealings with Washington and leads us to adopt what may be an unduly sensitive attitude.

Such last-minute thinking also tended to preclude much thought being given to cooperation with Canada’s more natural partners, including Australia.

In the meantime, Australia had faced a federal election in December 1949, and the Chifley Labour government had been replaced by a Liberal (conservative) government led by Robert Menzies. Ironically, like the St. Laurent government in Canada, Australia’s Menzies was initially reluctant to send troops to Korea. Menzies’ concern was to keep troops available for the Middle East, while St. Laurent was concerned about the threat in Europe. Yet both governments’ views were consistent with the strategic contingency plans that envisaged Korea as a possible precursor to the outbreak of a wider war. But in Menzies’ absence while travelling, his External Affairs Minister, Percy Spender, quickly responded to the news that Britain was preparing to commit forces. Australia thus announced a contribution, seeing that a commitment of forces to the conflict would have a positive diplomatic effect on its relationship with the United States.

Force Contributions

Thereafter, under Menzies, Australia quickly committed a squadron of aircraft and several ships to the conflict. The Mustang fighter aircraft of the Royal Australian Air Force’s 77 Squadron was the first of the British Commonwealth forces in action on 2 July 1950, and had the first British Commonwealth serviceman killed in the Korean War. The RCAF’s 426 Squadron joined the American airlift to Tokyo in late July 1950 (they stayed until 1954), but Canada’s air contribution was primarily through some twenty pilots and several technical officers seconded to the US Air Force. These men were credited with a total of more than twenty Russian-made jet fighters destroyed or damaged.

Having stationed forces as the lead participant in the British Commonwealth Occupation Force in Japan (known as BCOF) since 1946, Australia was relatively well placed to promptly contribute air, sea and ground elements to the conflict, even though the force had been scaled back in 1948 and the skeleton force that remained was about to completely withdraw as war broke out in Korea. Australian and Canadian naval ships also joined the fight early on, and comfortably integrated under the operational control of the Royal Navy in the Yellow Sea, or in Task Force 77, under the United States Navy, in the Sea of Japan. Both also contributed ships to the Inchon landings near the South Korean capital of Seoul in September 1950. However, Australia sent a smaller number of ground combat troops than Canada. Yet there was greater awareness in the United States of the more vocal and well-publicized Australian contribution than there was of Canada’s, with Australian troops having arrived in Korea five weeks before the Canadians landed.

That greater awareness sprang in part from the fact that Australia announced its commitment, along with the British and New Zealanders, before Canada did. In fact the announcements from these three countries prompted the Canadian Cabinet to review the Canadian position. Then, on 7 August 1950, the Canadian government announced its decision to recruit a brigade-sized Canadian Army Special Force, including three infantry battalions, each designated the second battalion of Canada’s three Active Force infantry regiments. In addition, the force included a regiment of artillery, a field ambulance, an infantry workshop, a transport company, and two light aid (field repair) detachments. The first element to deploy would be the 2nd Battalion, Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry (2 PPCLI).

AWM ART 28996

The RAAF’s first operation over North Korea, 2 July 1950.

Painting by Robert Taylor.

On 18 February 1951 2 PPCLI joined the 27th Commonwealth Brigade under a British commander. This formation for the most part used common British-pattern equipment and organizations, and included infantry battalions from Australia, Canada, England and Scotland, as well as a New Zealand field artillery regiment and an Indian field ambulance. The Canadians had contemplated re-equipping with items of US origin, but with the majority of the force consisting of Second World War veterans, most of their expertise would have been nullified by having to retrain on unfamiliar equipment. It therefore seemed more than reasonable for the Canadians as well as the Australians to retain the British-patterns. Up to that time there had been no record of any other brigade—or force of similar size—composed of so many contingents of different Commonwealth countries. Incidentally, such an arrangement would not be repeated until after the end of the Cold War, when the International Force in East Timor known as INTERFET constituted its ‘Westforce’, based on the Australian 3rd Brigade. This later formation would include two Australian infantry battalions, a New Zealand Infantry battalion, a reinforced company of British Gurkhas, a reinforced company of Canadian ‘Van Doos’ and a platoon of Irish Rangers.

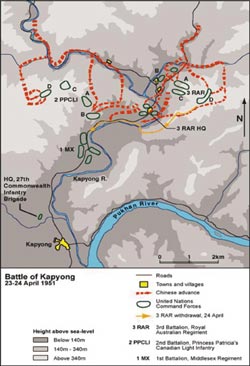

The Battle of Kap’Yong

In the meantime, from February 1951 onwards, following the arrival of 2 PPCLI in Korea, the Australian and Canadian land forces fought alongside each other for the first time since 1918. A couple of months later, in April 1951, near a place called Kap’yong, a significant battle took place. The battle was fought on a cleft between two promontories that marked one of the invasion routes into South Korea. While part of the 27th Commonwealth Brigade, 2 PPCLI, and the 3rd Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment (3 RAR), earned United States Presidential Unit Citations for their combined role in blunting a Chinese offensive. They did so alongside the New Zealand gunners and troops from the 72nd US Heavy Tank Battalion. Intelligence reports indicated that the attack had been launched by an estimated 6,000 troops from two Chinese regiments. Canadian and Australian accounts provide little coverage of, or even comparison with, each others forces, despite their very similar experiences and the fact that the outcome would not have been successful without their combined efforts. While Australian troops bore the brunt of the Chinese attack for the first part of the battle, they would have been easily outflanked and cut off had they not been effectively supported by the Canadian battalion on their left flank. When compared with the fate of the British Gloucestershire Regiment nearby on the Imjin River, the combined feat of arms at Kap’yong is put in stark relief. At the same time as the battle of Kap’yong was unfolding, the Gloucesters, essentially alone and surrounded by Chinese forces, were eventually overwhelmed. Perhaps a similar fate would have eventuated for the Australians and Canadians had they not been defending in mutual support of each other.

Used with permission.

The Battle of Kap’yong,

map by Lieutenant Slade Crooks (CF).

The Battle of Kap’yong was not just a Canadian or Australian feat of arms. It was the second ‘ABCA Battle’ involving a US tank battalion, a New Zealand artillery battery, as well as a British infantry battalion in depth, all under a British brigade commander.

The 1st Commonwealth Division

Subsequently, Canada and Australia both contributed forces to the only integrated ground formation of Commonwealth countries — the 1st Commonwealth Division — in mid 1951. This occurred despite the St. Laurent government’s initial reluctance to have Canadians grouped with the other Commonwealth forces, as St. Laurent preferred instead to stress Canada’s United Nations affiliation. The Division included an integrated British, Canadian, Australian and New Zealand headquarters as well as divisional and line-of communications signals units. The Canadian official historian observed that:

...The division achieved a remarkable degree of homogeneity. A formidable fighting force of over 20,000 all ranks, it remained to the end of hostilities a key formation along the line of hills defending the 38th parallel.

Canada’s main contribution as part of the division, the 25th Canadian Infantry Brigade, was commanded by an Australianborn veteran commander of Canadian troops in the North-West Europe campaign of the Second World War, Brigadier John M. (‘Rocky’) Rockingham. Thereafter, the Division had three brigades: one British, one Canadian and one predominantly Australian (with British and New Zealanders included). These brigades took turns in defensive positions along the Imjin and Sami-ch’on rivers near the 38th Parallel — including the well fought-over ‘Hook’ area. In addition, the predominantly British divisional support units incorporated Canadian, Australian, New Zealand and Indian members in their organizations.

Occasionally, Australian infantry units complained when taking over from the Canadians that Canadians had not dominated No Man’s Land by patrolling. According to Canadian historian, David Bercuson, “Canadian commanders were guilty of using inappropriate patrol tactics, of generally allowing patrols to become routine and meaningless, and primarily, of inadequate reconnaissance. All these failings can be linked to the absence of an effective patrol doctrine.” One Canadian officer reflecting on the fighting in March 1953 declared:

Our tactics have a stereotyped quality that deprives us of initiative and forewarns the enemy. We rarely trick the Chinaman. We do not use deception and have lost our aggressive spirit. Commanders and men are dug-out minded. The fear of receiving casualties deadens our reactions and lessens our effort. We are thoroughly defensive minded but not thorough in our defence.

On occasion, this mindset allowed the Chinese to prepare detailed assaults from No Man’s Land. For instance, on 23 October 1952, B Company 1 RCR’s position at Hill 355 (known as ‘Little Gibraltar’) was briefly overrun but retaken, albeit with significant casualties.

In contrast, the Australians had developed a tradition of patrolling and dominating No Man’s Land as a form of aggressive defence. This approach had been illustrated in the successful defence of the North African city of Tobruk in 1941—where a German armoured/infantry thrust was effectively stopped for the first time in that war by Australian infantry and British artillery. At Tobruk, dominance of No Man’s Land and the fearless and meticulous investigation of the terrain had become an Australian forté. In contrast to the Canadians, according to Australian historian, Jeffrey Grey, the Australians in Korea “erred in the other direction, patrolling too aggressively” and exposing themselves to greater casualties by straying into places from which it was difficult to extricate. Other complaints aimed by Australians at the Canadians were that they left their positions in unsanitary conditions, and with the camouflage and concealment weakened by the disposal of rubbish (including reflective tins) on the forward slopes of defensive positions—thus making attractive targets. The Canadian response was that “they saw little point in trying to conceal their positions from the enemy, who certainly knew where every rifle pit and crawl trench was—as the Canadians in fact knew of the Chinese positions”. Bercuson observed that “the magnificent effort of the [Canadian] troops was undermined by an improperly prepared divisional front and poor defence doctrine.” For the Canadians this was strongly influenced by their experience fighting the Germans in Italy in 1943 and 1944, where the actions were more fluid and the requirement had not been for defence in depth. But Bercuson also noted “there was failure at the division level also. Commonwealth Division HQ never imposed a uniform defensive doctrine along its front.” Brigadier Jean Victor Allard was the Canadian Brigade Commander for the last three months of the war (and later CDS in 1966). Allard was active in rectifying many of the faults he observed in the third rotation of battalions on assuming command. He also was scathing about the preparedness of his soldiers, and critical of his company commanders who were “brave and loyal”, but rapidly rotated and lacking in knowledge of the defensive battle, particularly patrolling skills.

Despite these differences, the Commonwealth forces still supported each others’ battles as a matter of course, whenever possible. In October 1951, for instance, when the Australians in 28th Commonwealth Brigade attacked Hill 317 (Maryang Sang), north of the Imjin River, the 25th Canadian Brigade swept forward on the Australians’ left, seizing their designated objec-tives.

American Influences

Also, as alluded to earlier, during this period both had started shifting to equipment, if not doctrine, of US origin. However, the purchase of US equipment by both countries was kept to a minimum due to political and economic constraints arising from adverse national balance of payments that favoured the United States.

This disparity between the Australians and Canadians was most evident in terms of the contrasting financial arrangements. Canada was not a member of the Sterling Area and thus felt financially unconstrained by the arrangements made under BCOF. In addition, Canadians were certainly not attracted to the diet of mutton, bully beef and biscuits to which the Australians, New Zealanders and Britons were subjected. Not surprisingly therefore, the Canadians were alone among the Commonwealth units in making regular use of American food rations. In contrast, financial constraints pre-disposed the British and New Zealanders to work through the administrative arrangements in place from the war’s outset through their Sterling-Area partners, the Australians. But rations aside, the Canadians found that, like the British and New Zealanders, the ease of Commonwealth logistic arrangements, based on the Australian support elements originally located in Japan, meant that the establishment of a Commonwealth formation made eminent sense. This was particularly the case given the plethora of other national contingents — each with unique requirements that had to be imposed on the American supply system.

In addition, tactical differences between the Americans and the Commonwealth forces were particularly evident. The American approach to defensive positions, for instance, called for establishing a ‘Main Line of Resistance’ along the lower or forward slopes of the hills being defended. These lines were complemented by strongly held outposts that invited attack and resulted in heavy American casualties. In contrast, the Commonwealth troops shared the view that the best place to defend from was on the hilltops—or ‘Forward Defended Localities’—with all-round defence, interlocking fire plans, plunging fire for the lower slopes (instead of forward-placed ‘main lines’), and lightly-held standing patrols that could be withdrawn at short notice. When Commonwealth and American units replaced each other on the front, the result was a great deal of alteration of positions, with much unnecessary digging and filling. On the Hook, for instance, such alterations resulted in a compromise in the defensive positions that would be exposed by Chinese attacks.

For the Commonwealth troops, the view was held that any battle which caused equal casualties on both sides left the Chinese with the advantage. Indeed, US Army doctrine was often considered inappropriate for the smaller Commonwealth forces, including the Canadians and Australians. Like the US Marines, who drew on a smaller recruiting pool than did the US Army, the Commonwealth Division troops, for both manpower and political reasons, could not afford to sustain continuous heavy casualties likely to arise from “fool-hardy stunts which had no military purpose.” Such ‘stunts’ included defending outpost positions at any cost. This, according to the British commander of the 1st Commonwealth Division, Major-General Cassells, was what the US Army Corps commander had unsuccessfully called for from the Commonwealth Division. According to Grey, the US Army forces also manifested “the penchant for senior commanders to play squad leader.”

Such inclinations reflected a seeming reluctance to trust non-commissioned officers and a pre-disposition to micro-manage minor tactical incidents. This predilection was complemented by attrition or ‘meat grinder’ tactics aimed at negating the Chinese numerical superiority by taking advantage of overwhelming American airpower and artillery domi-nance. Such tactics required little finesse from troops on the ground. But exposure to this approach to warfare discouraged Canadians and Australians from abandoning their British-derived tactics in favour of the more expensive and resource-consuming US examples.

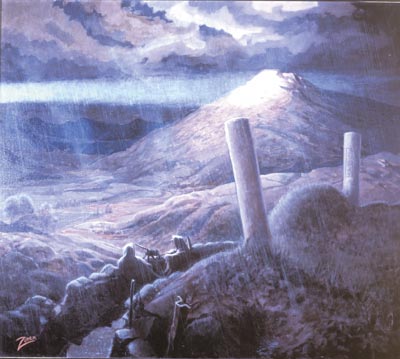

Canadian War Museum 90034

Bowling Alley. Painting by Edward Zuber.

Restraints On Cooperation

By late 1951, the entire 25th Canadian Infantry Brigade had deployed to Korea. Australia’s ground contribution peaked in 1952 with two infantry battalions in the 28th Commonwealth Brigade, a major contribution to the British Commonwealth Forces Korea support base and small groups assigned to divisional units. In August 1950, Brigadier F.J. Fleury had been appointed the senior Canadian officer in the Korean theatre. Fleury was therefore the founding head of the Canadian Military Mission, Far East. Fleury’s position involved considerable liaison with the Australians who were providing much of the administrative support. This support came largely from Japan through the Australian-led BCOF, the residual elements of which later formed its successor organization, the British Commonwealth Forces-Korea (BCF-K). Fleury had been invited to be the BCF-K Chief of Staff, and was eager to accept the appointment, but Canadian authorities preferred to limit his responsibilities, fearing such responsibilities would undermine his independence in safeguarding Canadian interests.

Grey points out that “it was an unfortunate decision” that led to occasional misunderstandings. Moreover, Grey argues, had Fleury been appointed, the “train of events surrounding the Koje-do incident [when Canadians were called in by US higher commanders, without consulting Ottawa, to help subdue prisoners of war who had seized a US-administered detention camp] might never have happened, and certainly would not have caught the Canadian government unprepared.” Canada’s official historian admitted later that although “Canada made too much fuss over the affair”, the real lesson was “the vital necessity for prior consultation between allies when unusual activity of any sort is being contemplated.”

Grey further observed that “personalities were as important as policies, with differences in the former often being used to justify disagreements in the latter.” Unfortunately such shortsightedness prevented key figures from seeing the merits in closer Australian-Canadian collaboration. For instance, the Canadians “were so concerned to preserve a distinctly Canadian position that they did not coordinate their actions with the Australians, to their mutual cost on occasions.”

After the armistice, Canadian and Australian troops would remain alongside each other as part of the composite Commonwealth force until the major combat units returned home in 1955 and the final elements were withdrawn in 1957. In the end, 26,791 Canadians served in Korea, with 1588 casualties including 516 dead and 32 captured. Australia suffered 339 killed and 29 taken prisoner. Chinese and North Korean casualties were likely more than a million, while United Nations casualties numbered some 490,000, of whom 33,000 were Americans killed. South Korea suffered 66,000 soldiers killed.

The Diplomatic Front

On the diplomatic front, Canada and Australia were included in the United Nations Committee of Sixteen, which started meeting in Washington in January 1951. Denis Stairs observed that “there was considerable esprit de corps among the non-American participants, but there was never advance collusion against the American officials. The Canadians, British, and Australians were especially close and often lunched together beforehand for general discussion, but the views even of these three were seldom unanimous.” Stairs further observed that:

Canadian diplomacy during the Korean War can be interpreted very largely as a manifestation of the attempt to support the core, while simultaneously containing the extremities of American policy, and to ensure that military forces operating under UN auspices, but delegated to US command, were prevented from being drawn into a larger Asian war.... The central preoccupation of senior Canadian policy-makers was ... they wanted the Americans to stop acting—or at least to stop appearing to act—unilaterally. ... [But] the Americans were paying most of the piper’s bill. It followed that they were calling most of the piper’s tunes.

Complementing the diplomatic manoeuvring was the tactical actions of troops such as the Canadians and Australians that proved so costly in lives, but which also had some significant strategic effects. For instance, it was during the Korean War that Australia and New Zealand negotiated a military alliance with the United States. The ANZUS Pact had become negotiable thanks to the re-assessment of American strategic security interests following the outbreak of the Korean War and thanks to the military cooperation offered to the United States in conducting it. The Treaty was signed during the month that Australia decided to commit an additional infantry battalion to Korea, and shortly after the combined Canadian and Australian successes at Kap’yong. The treaty was ratified in 1952, although it did not include military planning staffs or dedicated troops as NATO did, nor did it include an automatic commitment of support in time of crisis.

In addition, as Australian historian Glen Barclay observed: “Probably nobody in Canberra had ever conceived an alliance with the United States as a partnership between equals.” Still, it had the effect of reassuring Australians over the non-puni-tive terms of the peace with Japan. The treaty also justified limiting Australian defence expenditure, much as the American presence assured Canadians that they could afford to restrict defence expenditure. As Australia’s official Korean War historian, Robert O’Neill, observed, “The major dividend of participation was diplomatic rather than military or strategic.”

The ANZUS Pact also pointed to the growing focus of the Australian forces on increased interoperability with their US counterparts, much as their Canadian counterparts were also doing. Interestingly, Canada’s Conservative Party in the House of Commons also had considered joining an anti-communist Pacific Pact to complement Canada’s membership in NATO. The British floated the idea of a joint Commonwealth military presence in Malaya or Hong Kong. Australia and New Zealand joined, but despite its shared Pacific coastline and enduring interests in Asia-Pacific security, Canada still considered itself primarily a North Atlantic nation. Consequently, NATO would remain the priority for the remainder of the Cold War and beyond.

Nonetheless, what emerged from the Korean War for the Australian and Canadian forces was, for the first time in their histories, professional expeditionary forces, the leaders of which at all levels were experienced, combat-tested veterans. The Korean War had once again demonstrated that despite the predilection for gravitating towards the United States in terms of equipment and procedures, the Canadians and Australians would continue to find their own ways of conducting military operations more suitable and more like each other’s than that of their big uncle’s. The subsequent 50 years would see the concept of maintaining professional expeditionary forces undergo significant challenge and reorganization, but it would remain a proven and enduring instrument of state—for peacekeeping, war-fighting, and the plethora of ‘grey area’ missions in between that Canadians and Australians would be repeatedly called upon to perform.

Canadian War Museum 90033

Incoming. Painting by Edward Zuber, depicting shelling on the position of B Company, 1 RCR prior to a Chinese attack on Hill 355, 23 October 1952.

Reflections On the Canadian and Australian ‘Ways of War’

As observers reflect not only on the shared Korean War experiences of Australia and Canada, but also on other missions to which they have both contributed, a remarkable sense of déjà vu emerges. The overall trajectory of these two countries’ armies reflects a parallel attempt to grapple with the issue of professionalism and the military.

This dual-track approach left both countries ill-prepared for the military crises in 1914, 1939 and 1950. In addition, throughout the early 20th century both countries were gradually discovering their self-interests and learning how to ‘serve two masters’ — Britain and the United States. Not surprisingly, similarities are evident in force structures and in their relatively small size, limited funding, and modus operandi. These similarities were evident despite at times contrasting Canadian and Australian foreign policies.

While similarities were numerous, differences were equally apparent. For instance, both Canada and Australia developed their own ‘way of war’ that was strongly influenced by British models, but their experiences and their outlooks left different legacies. The Australian way was influenced by their experiences in the Middle East with desert warfare during both World Wars, where battlefield manoeuvre was both feasible and more common than the Canadian troops had experienced in Italy and North-West Europe.

The Australian way also featured fighting in the jungles to the north of Australia, where light forces, limited availability of artillery (and a concomitant increased reliance on air support instead), and small-team actions, including assertive patrolling, featured prominently. For much of the time such tactics were driven by resource constraints due to shortages in suitable equipment and adequately trained personnel as much as by the inaccessibility of the inhospitable terrain where the fighting took place. The combination of these factors led to a greater emphasis by Australians on battle cunning and local initiative — an approach that would come to be considered ‘manoeuvrist’. Australia’s experience was similar to the 19th century Canadian Militia myth of the ‘petite guerre’ with its stealthy hit-and-run raids that had its roots in the wars of conquest in North America of the 17th and 18th centuries. Yet even with the different approaches in Korea already noted, when contrasted with the experience and approach of their American allies, the differences between the Canadians and Australians would be placed in proper perspective — being quite minor.

After the Korean War, while divergence would become more apparent, particularly in terms of where Canadian and Australian forces focused their efforts, similarities between the two nations’ armies would indeed endure. For instance, Canada and Australia adhered to a short war, forces-in-being military doctrine that placed priority on ready regular forces instead of militia-based reserves. For Canada the focus was NATO and Europe, while for Australia it was the Middle East (for contingency purposes during the early-to-mid 1950s) and South-East Asia. Thereafter, neither Canada nor Australia felt they could disengage militarily from the outside world as they had done in the inter-war years, and both saw themselves as participants with other countries rather than independent military actors on the world stage.

With the advent of intercontinental bombers and missiles, Canada was no longer a “fire-proof house”, and Australia felt similarly about the prospect of possibly becoming the last ‘domino’ to fall following any southward Communist Russian or Chinese thrust. Such sentiments would permeate Australian and Canadian defence and foreign policy thinking for decades to come. This ‘forward defence’ approach to national security would also perpetuate the need for expeditionary forces.

Individually, their contributions at times would prove to be militarily peripheral. But even a superpower relies on multilateral support, and their combined contribution, on occasion, has been politically and militarily significant. The combined military feats of the Canadians and Australian forces — at Amiens in 1918 and at Kap’yong in 1951 — point to the synergy that can be gained by working together more closely. This presentation has also pointed to a series of missed opportunities to collaborate that may have provided increased military and diplomatic leverage.

Like ‘strategic cousins’, Canada and Australia continue to support international institutions and alliances; having contributed similar peacekeeping and war-fighting expeditionary forces for more than a century, while hardly recognizing each other along the way. Differences between the two remain but the contrasts belie the similarities. The shared experiences in the Korean War suggest that significant benefits may be gained from working more closely together in future, out of enlightened self-interest. The remarkable reconvergence witnessed since the end of the Cold War reinforces that view.

![]()

Lieutenant Colonel John Blaxland, Australian Army, until recently a Visiting Defence Fellow at Queen’s University, will receive a PhD in War Studies at the 2004 Spring Convocation at Royal Military College.

Notes

- See A.J. Hill, Chauvel of the Light Horse: A Biography of General Sir Harry Chauvel (Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1978) pp. 22–23 and 28–29; and Carman Miller, Painting the Map Red: Canada and the South African War 1899-1902 (Canadian War Museum and McGill-Queen’s University Press, Montreal & Kingston, 1993), pp. 224-230.

- Under General Rawlinson’s Fourth Army, the British III Corps on the left flank (including the 33rd American Division) and the French XXXI Corps also participated in the battle, tasked to conform to the advances made by the Canadians and Australians. See Gregory Blaxland, Amiens: 1918 (Frederick Muller, London, 1968), pp. 159, 163 and 191.

- John Blaxland, “The Armies of Canada and Australia: Closer Collaboration?”/”Les Armées du Canada et de l’Australie: Collaboration plus étroite?” in Canadian Military Journal, Autumn 2002.

- The hiatus in Australian-American security ties is explained in Roger Bell, Unequal Allies: Australian-American relations and the Pacific War (Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1977).

- Desmond Morton, “Interoperability and its Consequences”, in Robert H. Edwards and Ann L. Griffiths (eds.), Intervention and Engagement: A Maritime Perspective—Proceedings of a Conference hosted by the Centre for Foreign Policy Studies, Dalhousie University, and the Canadian Forces Maritime Warfare Centre, Halifax, 7-9 June, 2002 (The Centre for Foreign Policy Studies, Dalhousie University, Halifax, 2002), p. 160.

- T.B. Millar, Australia in Peace and War: External Relations 1788-1977 (St. Martin’s Press, New York, 1978), pp. 200-204.

- Ibid., p. 205.

- Canada House of Commons Debates 4 September 1950 and 8 June 1950, cited in Rear-Admiral Fred W. Crickard, “A Tale of Two Navies: United States Security and Canadian and Australian Naval Policy During the Cold War” (Master of Arts thesis, Dalhousie University, Halifax, September 1993), pp. 88-89.

- A useful overview of the Commonwealth countries’ military contributions to the Korean War is Jeffrey Grey’s The Commonwealth armies and the Korean War (Manchester University Press, Manchester, 1988). More recently, he along with Peter Dennis edited The Korean War: The Chief of Army’s Military History Conference 2000 (Australian War Memorial, Canberra, 1985). The authoritative Australian account is Robert O’Neill’s two-volume work Australia in the Korean War 19501953 (Australian War Memorial, Canberra, 1985). Canada’s is Lieutenant-Colonel Herbert Fairlie Wood, Strange Battleground: Official History of the Canadian Army in Korea (Queen’s Printer, Ottawa, 1966). More recent and less restrained is David Bercuson, Blood on the Hills: The Canadian Army in the Korean War (University of Toronto Press, Toronto, 1999).

- James Eayrs, In Defence of Canada: Growing Up Allied (University of Toronto Press, Toronto, 1980), p. 62.

- Major Graeme Sligo, “The Development of the Australian Regular Army, 1944-1952” in Peter Dennis & Jeffrey Grey (eds.), The Second Fifty Years—The Australian Army 1947-1997: Proceedings of the 1997 Chief of Army’s History Conference (School of History, University College, Australian Defence Force Academy, 1997), pp. 40 and 44-45.

- Eayrs, In Defence of Canada: Growing Up Allied, p. 62.

- Denis Stairs, The Diplomacy of Constraint: Canada, the Korean War and the United States (University of Toronto Press, Toronto, 1974), pp. x-xi.

- Council Office, ‘Survey of relations between Canada and the United States’, dated June 20, 1951 (copy in possession of author).

- Albert Palazzo, The Australian Army: A History of its Organisation (Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 2001), p. 218; Glenn St J. Barclay, Friends in High Places: Australian-American diplomatic relations since 1945 (Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1985), p. 40; and Stairs, The Diplomacy of Constraint, p. 196.

- George Odgers, Across the Parallel: The Australian 77th Squadron with the United States Air Force in the Korean War (William Heinemann Ltd., Melbourne, 1953), pp. 28 and 57.

- Wood, Strange Battleground, p. 179.

- Crickard, ‘A Tale of Two Navies’, p. 14; and Wood, Strange Battleground, p. 13.

- Odgers, Across the Parallel, p. 90.

- Barclay, Friends in High Places, p. 45.

- That is, the Royal Canadian Regiment (RCR), the Royal 22e Regiment (R22eR) and Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry (PPCLI).

- Wood, Strange Battleground, pp. 22-27 and 34.

- Ibid., p. 37.

- Ibid., p. 78.

- For engaging tactical accounts of the battalion battles fought by the Australians and Canadians see Hub Gray, Beyond Danger Close: The Korean Experience Revealed—2nd Battalion Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry (Bunker to Bunker Publishing, Calgary, Alberta, 2003); Bob Breen, The Battle of Kapyong: 3rd Battalion, The Royal Australian Regiment Korea 23-24 April 1951 (Army Doctrine Centre, Sydney, 1992); and O’Neill, Australia in the Korean War, 1950-1953, pp. 131-160.

- For a gripping account of the Gloucester’s battle, see Anthony Farrar-Hockley, The Edge of the Sword (Muller, London, 1954).

- Technically, with a separation of three kilometres between the 3 RAR and 2 PPCLI positions, the two battalions could not provide ‘mutual support’ with their direct fire weapons. But essentially the gap between their positions, considered crucial for the Chinese advance, could not be by-passed without clearing the features held by both battalions.

- Grey, The Commonwealth armies and the Korean War, p. 92; Stairs, The Diplomacy of Constraint, pp. 198 and 203; Wood, Strange Battleground, pp. 14 and 117-118; and John Blaxland, Signals Swift and Sure: A History of the Royal Australian Corps of Signals 1947-1972, (Melbourne, Royal Australian Corps of Signals, 1999), pp. 67-69.

- Wood, Strange Battleground, p. 133.

- Bercuson, Blood on the Hills, pp. 37-40.

- Grey, The Commonwealth armies and the Korean War, pp. 103-105; and Wood, Strange Battleground, pp. 181-211.

- O’Neill, Australia in the Korean War, 1950-1953—Volume II: Combat Operations, p. 253.

- Bercuson, Blood on the Hills, p. 193.

- Lieutenant-Colonel J.G. Poullin, CO 3 R22eR, cited in Bercuson, Blood on the Hills, p. 210.

- The Canadians suffered 18 killed and 35 wounded from the incident. See Bercuson, Blood on the Hills, pp. 188-190 and 204-207; Wood, Strange Battleground, p. 210; and Grey, The Commonwealth armies and the Korean War, p. 151.

- For an excellent synopsis of the techniques used at Tobruk see John Coates, Bravery Above Blunder (Oxford University Press, Sydney, 2000), pp. 11-43.

- Grey, The Commonwealth armies and the Korean War, p. 153.

- Ibid., pp. 150-151.

- Bercuson, Blood on the Hills, p. 182.

- Ibid., p. 160.

- Ibid., pp. 212 and 224-225.

- Gregory Blaxland, The Regiments Depart: A History of the British Army, 1945-1970 (William Kimber, London, 1971), p. 190.

- This point is argued in the case of Canada in Jon B. McLin, Canada’s Changing Defense Policy: the Problems of a Middle Power in Alliance (Johns Hopkins Press, Baltimore, with the Washington Center of Foreign Policy Research, School of Advanced International Studies, Johns Hopkins University, 1967), p. 172.

- Stairs, The Diplomacy of Constraint, p. 201.

- Grey, The Commonwealth armies and the Korean War, p. 172.

- Stairs, The Diplomacy of Constraint, p. 201.

- Wood, Strange Battleground, pp. 215-216.

- Ibid., p. 232.

- Grey, The Commonwealth armies and the Korean War, pp. 139-140 and 144.

- Bercuson, Blood on the Hills, p. 83.

- Grey, The Commonwealth armies and the Korean War, pp. 111-112; and Wood, Strange Battleground, p. 112.

- Bercuson, Blood on the Hills, pp. 199-202; Wood, Strange Battleground, pp. 191-196; and Grey, The Commonwealth armies and the Korean War, p. 114.

- Wood, Strange Battleground, p. 196.

- Grey, The Commonwealth armies and the Korean War, p.131.

- Wood, Strange Battleground, pp. 244 and 250; David J. Bercuson & J.L. Granatstein, Dictionary of Canadian Military History (Oxford University Press, Toronto, 1992), p. 111; and Peter Dennis, et. Al., (eds.) The Oxford Companion to Australian Military History (Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1995), p. 336.

- Stairs, The Diplomacy of Constraint, pp. 138-139.

- Denis Stairs, “Canada and the Korean War Fifty Years On” in Canadian Military History (Volume 9, Number 3, Summer 2000), pp. 52-53 and 58.

- David Horner, Defence Supremo: Sir Frederick Shedden and the Making of Australian Defence Policy (Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 2000), p. 307; and Alan Watt, The Evolution of Australian Foreign Policy 1938-1965 (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1967), pp. 120-121.

- Watt, The Evolution of Australian Foreign Policy 1938-1965, pp. 125-127.

- Barclay, Friends in High Places, p. 49.

- O’Neill, Australia in the Korean War, Vol II, p. 409.

- Eayrs, In Defence of Canada—Indochina: Roots of Complicity, p. 47.

- Bercuson, Blood on the Hills, p. 221.

- Wood, Strange Battleground, p. 258.

- The Australian Army, The Fundamentals of Land Warfare—LWD1 (Land Warfare Development Centre, Puckapunyal, 2002), Chapter 4.

http://www.journal.forces.gc.ca/vo4/no4/lecture-conferen-eng.asp